A lot can go wrong when we measure ourselves against bogus standards, standards that cannot be met because they are not real. They are fake, false, fraudulent, phony.

A lot can go wrong when we measure ourselves against bogus standards, standards that cannot be met because they are not real. They are fake, false, fraudulent, phony.

An early whistle-blower picked up the scent of Bernie Madoff’s fraud when his boss asked him why he was not achieving similar returns. Attempting to unlock the secrets of Bernie’s “genius” investment strategy by reverse engineering it over the years, he quickly came to the conclusion that it was impossible. Unfortunately, others did not do the same homework (and the SEC did not listen to said whistle-blower’s repeated warnings). Thus the markets pushed and pushed everyone to achieve stunning “above-average” returns year after year. Of course it is mathematically impossible for the majority of the market to achieve above-average returns. Yet that is what the markets demanded, so that it was what the markets “got.” But they “got it” by running extraordinary risk and they “got it” by accounting machinations, some legal, if not too ethical, and some downright shady. As the saying goes: When you push people too hard to make the numbers, sooner or later they start to make up the numbers.

So, reality please. It may not always be what we want to hear, but it is what we always need to hear.

And reality across the board.

– A “Reality Please” dart to the glamour industry for making the use of Photoshop the norm. “’It now seems fresh, even exclamation-worthy, when a magazine presents an unvarnished image. Last month, for example, an issue of Life & Style took the unusual step of declaring that a cover photograph of Kim Kardashian was ‘100 percent unretouched,’ as if it had done a great service to the cause of pseudo-celebrity journalism. And People, in its ‘100 Most Beautiful’ issue this month, included images of 11 celebrities ‘wearing nothing but moisturizer.’” (The New York Times, May 28, 2009, “Smile and Just Say No Photoshop,” below.) False realities in financial markets lead to fraud and burst bubbles. Impossible standards of “beauty” as social norms lead to bulimia, anorexia, damaged self-image, and shaky self-esteem, particularly in the young and emotionally vulnerable.

– A “Reality Please” gold star to our new First Lady for having the guts to be authentically human: “’There isn’t a day that goes by,’ Mrs. Obama told a panel of young women at Howard University earlier this year, ‘that I don’t wonder or worry about whether I’m doing the right thing for myself, for my family, for my girls.’ Johnetta Boseman Hardy, who organized that panel, was stunned. ’She’s letting people know: It’s O.K. to say that working motherhood is a challenge; it’s O.K. to say that I don’t have all the answers,’ said Ms. Hardy, a working mother who heads Howard University’s Institute for Entrepreneurship, Leadership and Innovation. ‘I didn’t expect her to be that real.’” (New York Times, May 28, 2009, “On the Home Front, a Little Candor.”)

By having the courage to be honest, by not pretending to be perfect or to have all the answers, by admitting to having normal human doubts, issues, and frailties, Mrs. Obama makes it easier for all of us to feel it is okay to be human. And that’s good, because in the final analysis, behind our posturing and our masks, we are human. And that’s just reality.

———————-

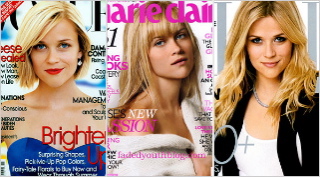

Photo caption: What’s new? Images of Reese Witherspoon show how a celebrity’s appearance can change radically from cover to cover.

Smile and Say ‘No Photoshop’

Most readers of fashion magazines are aware that all photographs, at least to some degree, lie.

By ERIC WILSON

The New York Times

Published: May 28, 2009

More often than not, images have been altered — historically with painstaking tricks of lighting and exposure and, more recently, with retouching software that can make celebrities and models look thinner, taller, unblemished, with brighter eyes and whiter teeth. Seemingly perfect. Advances in digital photography have made it so easy to manipulate photographs that cover models often resemble weirdly synthesized creatures or, as the photographer Peter Lindbergh described them this week, “objects from Mars.”

No one could reasonably argue that Gwyneth Paltrow’s skin is indeed made of Silly Putty, as it appeared to be on the May 2008 cover of Vogue, or that Jessica Simpson’s body comes with only one hip, though her left one was suspiciously missing on last September’s cover of Elle, or wonder how the shape of Reese Witherspoon’s chin, dimples and eye color could change so drastically from her angelic Marie Claire appearance in February 2008 to her polished Vogue cover in November to her kittenish Elle pose this April.

Some popular blogs have made a sport of identifying egregious cases of Photoshop abuse, but the degree to which changes are made is rarely disclosed (and usually only when a magazine is caught). But as retouching has become more blatant and bizarre, sometimes resulting in bodies that defy the natural boundaries of human anatomy, a debate over photo manipulation has spilled into public view, with Mr. Lindbergh, one of the world’s most famous image makers, leading the charge against the practice.

“My feeling is that for years now it has taken a much too big part in how women are being visually defined today,” Mr. Lindbergh said in an e-mail exchange. “Heartless retouching,” he wrote, “should not be the chosen tool to represent women in the beginning of this century.”

Last month, Mr. Lindbergh stirred the pot by creating a series of covers for French Elle that showed stars like Monica Bellucci, Eva Herzigova and Sophie Marceau without makeup or retouching. The issue struck a nerve with readers in France, where health officials were already campaigning for a measure to force magazines to note when and how images are altered. But editors of American publications, who last year resisted such a proposal within their trade group, the American Society of Magazine Editors, have also noted a backlash against images that appear manipulated to push an idealized standard of beauty.

It now seems fresh, even exclamation-worthy, when a magazine presents an unvarnished image. Last month, for example, an issue of Life & Style took the unusual step of declaring that a cover photograph of Kim Kardashian was “100 percent unretouched,” as if it had done a great service to the cause of pseudo-celebrity journalism. And People, in its “100 Most Beautiful” issue this month, included images of 11 celebrities “wearing nothing but moisturizer.”

“Fashion magazines are always about some element of fantasy,” said Cindi Leive, the editor of Glamour, “but what I’m hearing from readers lately is that in fashion, as in every other part of our lives right now, there is a hunger for authenticity. Artifice, in general, feels very five years ago.”

Oddly, so does this debate. It was in 2003 that one of the most famous retouching controversies arose when Kate Winslet asserted that the British edition of GQ had excessively altered a photograph of her to make her look thin. That episode was followed by many more: Andy Roddick’s enlarged biceps on the cover of Men’s Fitness, Katie Couric’s streamlined promotional photos and the slimming of Faith Hill in Redbook, the latter exposed in a 2007 competition by the fashion Web site Jezebel to uncover retouching sins. Glamour, too, has faced photo-tampering accusations, including a charge, which the magazine denied, that it digitally shrank the actress America Ferrera on the cover of an issue in 2007 dedicated to techniques for readers to flatter their figures.

And yet a raw-celebrity movement has been slow in coming. That may be because, as several editors said privately, celebrities’ publicists almost always demand retouching of wrinkles and visible cellulite. As a result, a celebrity can look different from one magazine to the next.

“There’s no question that images have been altered so significantly that, at times, it’s so apparent it’s transparent, actually,” said Dennis Freedman, the creative director of W, a magazine that intentionally features photographs of both extremes: Juergen Teller’s patently unretouched portraits on one hand and the digitally stylized work of Mert Alas and Marcus Piggott on the other.

“These are covers that look like Breck ads,” Mr. Freedman said. “But my question is, did they intend for them to look like Breck ads? Is there irony? Is there subversion? Because there is no question they are retouched beyond any possible reflection of what’s actually in front of the camera.”

The ethical issues of retouching have been discussed at least since the 1930s, when George Hurrell manipulated characteristics of Hollywood actresses in photographs to make them into icons of glamour. But technology has changed the scope of the debate, fueling a long-held criticism that magazines are promoting an unattainable standard of beauty.

In the early 1990s, as the first programs for digital manipulation came into use, some art directors began exploring the potential for creating images with a heightened sense of reality, actually as a reaction against the prevailing images of supermodels that looked too perfect. They were interested in creating images like those achieved through special effects in movies. Magazines like The Face championed a style coined by its art director, Lee Swillingham (now the creative director of Love), as “hyper real,” with photographs by Norbert Schoener, Inez van Lamsweerde and Mert and Marcus that seemed to share an affinity with Mannerist paintings. Models were presented as grandes odalisques, with impossibly long necks, or waists reduced to sizes against nature. They were not suggesting that the look should be attainable.

“We were trying to create a future fashion,” Mr. Swillingham said. “You could do something that looked gritty and real or something that looked like plastic.”

No one could have predicted how quickly that future would come. Suddenly, images could be changed even as they were being made, replacing backgrounds and filters with the touch of a button, turning night into day. It follows, then, that the next logical step in fashion would be a reaction against all that. For a coming issue of Love, Mr. Swillingham just commissioned a shoot where the brief to Glen Luchford, the photographer, was to make images that look like his early work in 35-millimeter film, using a digital camera to recreate a pre-digital style of photography. Some cutting-edge photographers now say that they, too, would like to see images that are more real.

“Anybody with a few days’ experience on Photoshop can drop in a new background or remove a pimple off a girl’s nose,” said Phil Poynter, who shoots campaigns for Tommy Hilfiger and editorials for Love and Pop. Still, he noted, “the big discussion in the fashion business has always been about should we retouch girls, should we create a portrait of a girl that is not achievable by a real girl.”

That issue came up in a revealing moment from the recent “60 Minutes” profile of the Vogue editor Anna Wintour — actually from an outtake of Morley Safer’s interview with her that was posted online — when she described an Irving Penn photograph, used to illustrate an article about the dangers of obesity, as one of the most beautiful ever to appear in her magazine. The starkly lighted image shows not a model in haute couture but an obese woman who is naked.

“It’s the kind of picture that really is going to make people stop and pay attention and have them just be provoked, which was really the point,” Ms. Wintour told Mr. Safer.

The implication here is that what can be considered a provocative image in a fashion magazine today is one that shows something real.

Undoubtedly, the most compelling photographs are ones that show real character, said Mr. Freedman of W. Nevertheless, he questions whether there will be a remarkable change as a result of the media attention following Mr. Lindbergh’s French Elle covers. Fashion magazines, to some extent, thrive as an escape from reality, a window to something that exists outside the ravages of time.

“I wonder how long that’s going to last,” he said. “It raises an interesting point, but that in and of itself becomes a kind of gimmick. I would not bet my life savings that it is something they are going to continue.”

0 Comments