Normally, it takes 3 full years to get a J.D. degree (Juris Doctorate or Doctor of Law) and 2 years to get an M.B.A. Frequently summers are spent on internships related to one’s field of study. A while back, joint J.D./M.B.A. programs came into vogue, attempting to combine the two degrees, somehow cramming 5 years worth of learning into 4 years. I’ve always viewed these joint J.D./M.B.A. degrees with a jaundiced eye. Quite frankly, the current education length is a compromise with the constraints of reality. Even 3 years is not enough to become a good lawyer and the idea of becoming a “master” of business in 2 years is ludicrous.

Normally, it takes 3 full years to get a J.D. degree (Juris Doctorate or Doctor of Law) and 2 years to get an M.B.A. Frequently summers are spent on internships related to one’s field of study. A while back, joint J.D./M.B.A. programs came into vogue, attempting to combine the two degrees, somehow cramming 5 years worth of learning into 4 years. I’ve always viewed these joint J.D./M.B.A. degrees with a jaundiced eye. Quite frankly, the current education length is a compromise with the constraints of reality. Even 3 years is not enough to become a good lawyer and the idea of becoming a “master” of business in 2 years is ludicrous.

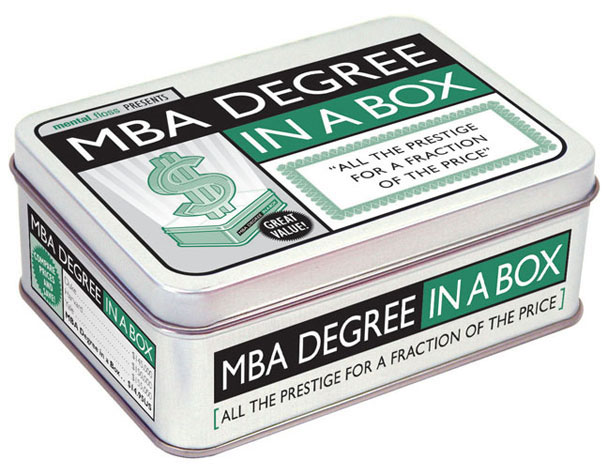

Joint J.D./M.B.A. degrees are inevitably “knowledge-lite,” nothing more than catchy marketing labels. What you really have is a business degree with a heavy law minor or a law degree with a strong business minor. Slimmed down, watered down, cut rate, discount versions of the Real McCoy. I do not quite understand how 5 years worth of knowledge can be acquired in 4. Even if some of the hours are added by going to class in the summer, it is at the expense of the exceedingly valuable education of real-world, hands-on experience provided by relevant internships. Another casualty of condensed programs are extracurricular activities, such as law review or business clubs, that also add significantly to the education experience.

This blog is prompted by a Wall Street Journal article (below) about some schools diluting the quality of J.D.s and M.B.A.s by even FURTHER reducing the timeframe required, from 8 semesters to 7, far fewer then the traditional 10 semesters required if done separately.

Larry Kramer, dean of Stanford University Law School said it well in explaining why Stanford rejected the idea: “We considered it because of the competition for students,” says Mr. Kramer. “Unaltered, the programs are five years’ worth of study. To cut 40% was just not responsible.”

We all have purchased products marketed in fancy packages and then been disappointed to find upon opening that the actual contents are significantly less than the size of the package would lead you to expect. Same principle applies: you can call it a joint J.D./M.B.A. all day long, but calling it so doesn’t make it so.

FULL DISCLOSURE: I have both an M.B.A. (1978) and a J.D. (1982) obtained the old-fashioned way, one at a time, from the University of Florida. I actually took 3 years to get my “two year” M.B.A., this being back before the university closely monitored credit hours. I love to learn so I amassed a rather large number of excess elective hours, including enough graduate-level accounting classes to substitute for the traditional years’ experience required to sit for the C.P.A exam. I also took a couple of law school tax courses while enrolled in the M.B.A. program. While it was long before joint J.D./M.B.A. programs became the “in” thing, in an effort to encourage well-rounded learning, the university, in theory, allows any graduate student to enroll in any graduate course (prerequisites are another issue) in any college. I had taken all the tax courses the business school had to offer and when someone told me the really tough tax courses were offered at the law school, I took that as a challenge and wandered over to the law school. The registrar clerk looked at me as if I were nuts. Evidently no one had ever actually done it, but they handed me some papers and told me if I could get the professor to sign off on it, I was in. I was thoroughly over my head. The law looks at the world altogether differently from business but I buckled down and studied hard and made a B. When I did finally attend law school I felt that my “preview” experience gave me a slight head start over the other incoming first year students.

————

Creating a Shorter Path to a J.D./M.B.A.

By DIANA MIDDLETON

The Wall Street Journal

May 20, 2009

Joint law and business degrees — the J.D./M.B.A. — have long catered to a small group of students looking to pursue specialized, blended careers with outside expertise. The joint degree, offered at some 42 schools, is billed as a rigorous combination of legal and management studies that has usually taken four years to earn.

Typically, only a handful of students enroll at any given school, and lately, that number has dwindled thanks to students’ growing desire to jump back into the work force faster. Total enrollment in such programs fell from 330 to 287 students between the 2005-06 and 2007-08 school years, according to a recent survey by AACSB International, which accredits business management and accounting programs.

In response, a handful of schools are offering fast-tracked, condensed programs. At a time when students are wary of spending four years ensconced in books when they could be earning a living, some programs are slicing as much as a year off their requirements for the degree, including Northwestern University, University of Pennsylvania and Yale University.

Starting this fall, the University of Pennsylvania will offer a J.D./M.B.A. in seven semesters squeezed into three years (as opposed to the usual eight semesters over four years), including one summer semester between the first two years. Wharton Graduate Division Vice Dean Anjani Jain expects the new curriculum to more than double the number of J.D./M.B.A. students to 25. “A three-year hiatus from professional pursuits [is] more attractive to students than four,” Mr. Jain says.

Northwestern launched its condensed J.D./M.B.A. program in 2000, and has had a traditional four-year program since 1970. In the shorter program, students complete the core requirements for both the law and business schools and then cherry-pick electives from either curriculum. This year, applications shot up 50% to 250, says Beth Flye, director of admissions for the university’s Kellogg School of Management. The class entering this fall will have 30 students, up from 25.Yale will offer its coming three-year J.D./M.B.A. program without any required summer classes. The shorter joint degree aims to develop analytic and quantitative skills that are beyond what law schools traditionally offer, says Sharon Oster, dean of Yale’s School of Management. The four-year degree will still be offered but will go deeper into certain subjects.

“Someone who’s interested in a career in something specific, such as real-estate finance, would probably want to do a four-year,” Ms. Oster says. The additional year gives students ample time to dig into areas of interest with electives and extracurricular activities, she explains. “But for those who want something more general, the three-year is a great option.”

Some students who have already been through the lengthier programs say there is an appeal to a shorter program. David Hauser Cameron, a graduate of University of Pennsylvania’s J.D./M.B.A. program, parlayed his four-year degree into a career at the Hong Kong office of Linklaters, a British law firm specializing in financial services. He says the three-year option would have been difficult to resist, had it been available when he started the program in 2004.

“It would be hard to voluntarily sign up for an additional year,” he says.

Still, Mr. Cameron says there are advantages of a longer program. One is the added time for forming relationships with classmates and professors or spending time abroad. The multiple summers also allow students to “test-drive” multiple career paths.

Some of the shorter programs require students to take summer courses, meaning less time for internships. And students in three-year programs often have such jam-packed schedules they aren’t able to participate in law reviews or take as many elective courses.

What’s more, some administrators say that the full four years are necessary to adequately prepare for a career in either law or business, let alone for a potential career combining both.

Larry Kramer, dean of Stanford University Law School, says the school thought about shortening its four-year program to three years, but decided against it. “We considered it because of the competition for students,” says Mr. Kramer. “Unaltered, the programs are five years’ worth of study. To cut 40% was just not responsible.”

0 Comments